Calibrating career satisfaction

In the same way that control systems compare inputs and make adjustments to achieve desired outcomes, Mark Bedillion’s unconventional career path has been a well-managed control loop that has led to success and happiness.

Mark Bedillion’s professional journey to becoming a teaching professor was unconventional.

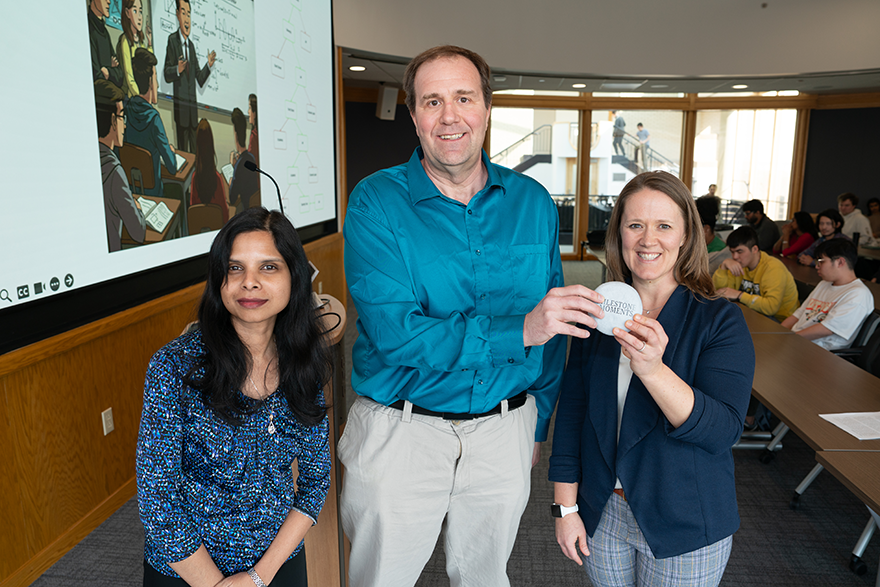

When he shared his unique career path with faculty, staff, and students from the College of Engineering at the recent Center for Faculty Success Milestone Moments program, it was obvious that he found both fulfillment and joy in his unique career trajectory.

“I haven’t taken the most direct path, but there is something to be gained from switching around,” Bedillion explained.

Bedillion’s lifelong philosophy has always centered around finding joy in whatever he was doing. In his early years, engineering wasn’t even on his radar. He jokingly recalls that unlike many would-be engineers, he didn’t like playing with Legos. Instead, Bedillion pursued his own passions—skateboarding, drumming, and history.

Source: College of Engineering

Mark Bedillion presents his Milestone Moments talk

Once he decided to study mechanical engineering, it was Professor Bill Messner who inspired him to specialize in control system. As an undergraduate student, Bedillion conducted research on power plant emissions with Mark Rubin and presented his first paper to the EPA in 1998.

After receiving his bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering, Bedillion considered graduate school, but chose to enter the workforce instead.

His first job after graduation was with Teradyne, an automatic test equipment manufacturer as a sustaining engineer, reworking old pieces of technology. This job came with some perks, like the opportunity to travel throughout Europe. In time, Bedillion realized that the more interesting work at Teradyne was being done by people with graduate degrees, so he decided to return to Carnegie Mellon and pursue his master’s and Ph.D. degrees.

Life is not an optimization problem.

Mark Bedillion, Teaching Professor, Director of Academic Operations, Mechanical Engineering

When he returned to Carnegie Mellon as a graduate student, it was once again Bill Messner who would ignite his passion for engineering. As a graduate student, he researched flexible manipulation systems and, ironically, took more courses in the Robotics Institute and in electrical and computer engineering than in mechanical engineering. While excelling in his research, Bedillion also excelled in the classroom, winning the Best Teaching Assistant Award twice during his time at CMU.

After earning his Ph.D., Bedillion again had to choose between a career in academia or in industry. He knew that he disliked writing papers and grant proposals, and getting up in front of students to teach made him anxious. So he leveraged some of his advisors’ connections and returned to industry.

Bedillion secured a position with Seagate, working as a research staff member, a servo-mechanical subsystem lead, and eventually a research engineering manager. He built disk drives, developed probe-based data storage and, through the many presentations he had to give, eventually overcame his fear of public speaking.

As with all his other positions, Bedillion made the most of his time with Seagate. He was excited by the work he was doing, he earned promotions within the company, and he enjoyed the financial bonuses that came his way. One downside of industry was the relative job instability he was seeing, which helped to convince him to leave industry and return to academia.

Bedillion accepted a position as an associate teaching professor at the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology. While there, he earned tenure and graduated his first Ph.D. student. He had really grown to enjoy teaching, but he still loathed writing proposals. So when a teaching track position opened up in CMU’s Mechanical Engineering Department, the prospect seemed very appealing despite having to forfeit his tenure for the teaching track position. Relocating again was well-timed because Rapid City, South Dakota had started to feel a bit too remote to him and his family.

He returned to the familiar streets of Pittsburgh and the Carnegie Mellon campus in 2016. Fittingly, one of the first courses he taught was Control Systems, the class that started his academic career in engineering.

Source: College of Engineering

L-R, Reeja Jayan, Mark Bedillion, Katie Walsh

Since then, Bedillion has taught a variety of courses and led several educational initiatives. Mark’s passion for engineering education has made a lasting impact on his students, something Mechanical Engineering Department Head Jonathan Cagan can attest to.

“He is a professor that genuinely cares about the overall development of students,” says Cagan.

His position as a teaching professor allows him to pursue his teaching interests while still maintaining a foothold in industry. Bedillion spends his summers working for Aerotech as a visiting researcher. This gives him a chance to, as he puts it, “be an engineer” and he brings these “real world” examples to his classroom. Students appreciate the opportunity to apply their knowledge to problems that they will face when they enter the workforce, and he enjoys the novelty that these summer months bring to his work.

Moving forward, Bedillion hopes to continue to learn throughout his career, primarily by teaching new courses. “I never fully understood the topic until I had to teach it,” he explains. Other than expanding the courses he teaches, Bedillion affirms that he is happy with where he is right now.

“Life is not an optimization problem,” he says. “I know people who have been promoted one too many times, and they are miserable. You can stop and say, I’m satisfied now.”