A buzz-worthy engineering design course

Civil and environmental engineering students learn the engineering design process by working with stakeholders to build habitats that protect local pollinator populations.

Many think of mason bees as pests—bothersome insects that nest in holes in your homes, decks, or wooden fences. But, if you ask Carnegie Mellon students in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, they might give you a different answer.

“They started seeing the bees as their clients,” said Katherine Flanigan, assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering and course instructor.

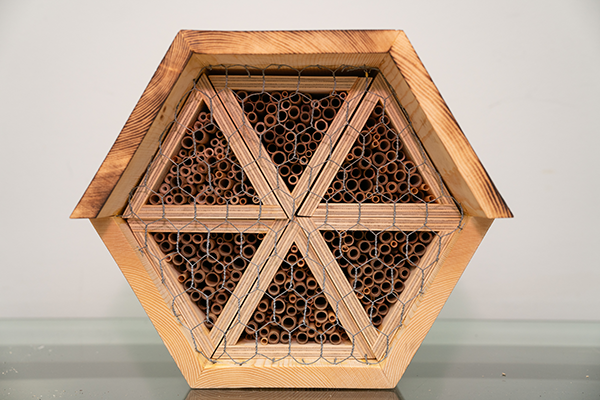

In the department’s sophomore year project course, the assignment was to design, build, and deploy homes for solitary, cavity nesting species of bees, including masons. The structures, commonly known as “bee hotels,” often look like large birdhouses with perforated fronts, made of many small holes stacked on top of each other for the bees to properly lay eggs. They provide safe and ideal conditions for the bees to reproduce, protecting species that are native to the Western Pennsylvania region and vital to the local pollinator ecosystem.

The project began with a trip to Phipps Conservatory and Botanical Gardens, a future home for one of the finished bee hotels, to learn more about the bees they were designing for. Quickly, the group realized that even the smallest stakeholders have big needs.

“Cavity nesting bees require very specific conditions to reproduce in their habitats,” said Braley Burke, integrated pest management specialist at Phipps and a client for one of the student groups. Burke recently purchased a mason bee hotel for the conservatory but found that many of these specifications often aren’t met with mass-manufactured bee houses.

“From the length and diameter of their cells to the materials used, the smallest error in design choice can enable the spread of disease, attract predators, and ultimately harm the species you’re trying to help,” she said.

Ideal bee hotels are made of untreated wood, avoiding materials like plastics, metals, and paints, with stacked straw-like cells filling in the middle. Cells should be between three to six inches long with a 3/32-to-3/8-inch diameter hole through the center. To protect the structure from the elements, a roof or overhang may be necessary, as well as a way to remove and clean the straws to prevent the spread of disease or infestation.

On top of nature’s constraints, the groups also needed to satisfy the requirements of the other interested parties: the gardens, parks, and nature centers across Western Pennsylvania and Ohio where the bee hotels would be deployed. Different stakeholders came with their own unique needs, including shape, size, aesthetics, and level of maintenance. Divided into six teams, instructors assigned a client to each student group and challenged them with the task of creating something that balanced their stakeholder’s needs and the bee’s environmental necessities.

They learned how engineering is applied in the real world.

Katherine Flanigan, Assistant Professor, Civil and Environmental Engineering

“We spent a month going over the engineering design process before they started building so they knew how to approach the project effectively,” said Flanigan. “They learned how engineering is applied in the real world with assignments like building a team contract, ranking stakeholder objectives, developing metrics to measure success, and producing engineering drawings.”

Once designs were approved and materials were ordered, students moved into the construction phase. Senior Project Engineer Brian Belowich, who also supervised the groups during this time, noted that most of the students were working in a woodshop and operating power tools for the first time. So, lessons like how to optimize their time with the tools and best use their materials to avoid waste were crucial.

This is what engineering is all about: envisioning something and making it a reality.

Brian Belowich, Senior Project Engineer, Civil and Environmental Engineering

“It’s exciting to watch them learn how to build something sustainably, efficiently, and safely because this is what engineering is all about: envisioning something and making it a reality,” said Belowich.

Several student groups made similar design decisions, including building removable cartridges to minimize the maintenance required by the stakeholders to keep the structure clean, increasing the lifespan of the bee houses by years. Two teams were so enthused by everything they learned about mason bees that they integrated QR codes into the side of their hotels for visitors to scan and learn more about their local pollinators. Only one group chose to drill holes into solid wood rather than using individual straws, a preference of their stakeholder.

All groups, however, began to see their job as serving two clients: the actual organizations and the mason bees. “A rationale I started hearing often in the shop was ‘I don’t think the bees will like that,’” said Belowich.

“I loved the entirety of the design process, from learning about mason bees and client needs to creating and choosing designs,” said Samhita Gudapati, a sophomore double majoring in environmental engineering and chemistry. Her group built a hexagonal bee hotel for Phipps Conservatory. “This class taught me valuable communication and presentation skills that I will definitely reference in internship, job, and classroom settings. But it was also just fun!”

Jonathan Subramanian, a sophomore studying environmental engineering, agreed. “The most memorable part was working with an outside stakeholder. Creating something that would be used outside the classroom by many groups of people and for an extended period of time was new and incredibly valuable to me,” he said.

This has been my favorite course so far at CMU.

Nurshinta Berry, Sophomore, Civil and Environmental Engineering

“This has been my favorite course so far at CMU,” Subramanian’s team member, Nurshinta Berry, shared. The group designed the most unique bee house from the course, drilling holes into solid wood over using individual bamboo tubes at the request of their stakeholder, Winthrop Community Garden.

“At first, we questioned the feasibility of the design. But after a lot of planning and reworking, we were able to make the client’s vision a reality, which was really exciting,” said Subramanian.

Now, as the bee hotels find their homes in gardens and parks across the region, the students’ hard work will play a meaningful role in supporting local ecosystems and benefitting both our pollinators and public spaces.