Democratizing air quality data at nearly no cost

Using existing filter tapes collected by U.S. embassies in Africa, mechanical engineering researchers have found a way to measure black carbon concentrations in fine particulate matter with only a reference card and their cell phones.

Due to the high cost of air quality monitors, many countries don’t have the tools in place to regularly monitor pollutants. Without routine measurements, policymakers cannot make evidence-based policy decisions to reduce fine particulate matter (PM2.5) exposure and improve human health.

To combat this problem, Albert Presto, research professor of mechanical engineering, has identified a low-cost way to quantify black carbon in PM2.5 using glass-fiber filter tapes that are already collected by select U.S. embassies around the world.

“For this project, we started with the Global South, because in Africa the need for air quality data is the greatest,” explained Presto.

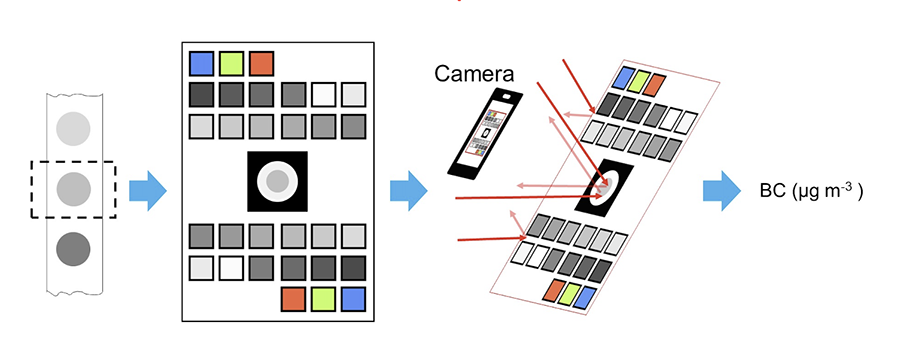

The team collected tapes from U.S. embassies in Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, and Ethiopia and compared their particulate matter to that collected from a site in Pittsburgh. To test air quality, the researchers photographed, using a cell phone camera, the filter spots on the tape on top of a custom-designed reference card. By applying an image processing algorithm to each photo, they could extract the red scale value of the photo. This value allows them to identify the air’s black carbon concentration during the hour of the day that the filter was collected.

The team detects black carbon on the tapes using cell phone camera photos.

Using this method, researchers can get a better understanding of pollutant sources. Black carbon is considered a “short term climate forcer” because of the way it absorbs light and consequently warms the atmosphere. For example, if deposited on a glacier, the glacier will melt faster.

The study’s findings underlined the need for more air quality monitoring in developing countries. The black carbon:PM2.5 levels in the Sub-Saharan African countries were as much as four times higher than those collected in Pittsburgh.

This method can democratize air quality data because there are plenty of groups that can collect tapes from other embassies and do their own analysis for practically no cost.

Albert Presto, Research Professor, Mechanical Engineering

“Our process is a new way to think about low-cost analysis,” said Presto. “Because the tapes are already being collected, the marginal cost for our analysis is near zero. This method can democratize air quality data because there are plenty of groups that can collect tapes from other embassies and do their own analysis for practically no cost.”

Source: AirNow Department of State

Presto’s team leverages existing PM2.5 measurements worldwide.

Presto is eager to both work with more embassies and explore what else his team can learn from the tapes. They are currently exploring a new way to extract the filters in a solvent to uncover exactly what else the PM2.5 is composed of throughout the day.

“There’s growing work in monitoring air quality from outer space, but to do that we need data collected on ground to validate the findings. Using this method, we can likely grow the number of locations where we can compare the satellites to data on the ground. We can also make more data available to countries around the world.”