A producer at heart

Alumna Julia Royall (DC ’73) has spent her life modeling a collegial approach through her work. Now, she is encouraging the next generation of interdisciplinary thinkers at CMU-Africa to do the same.

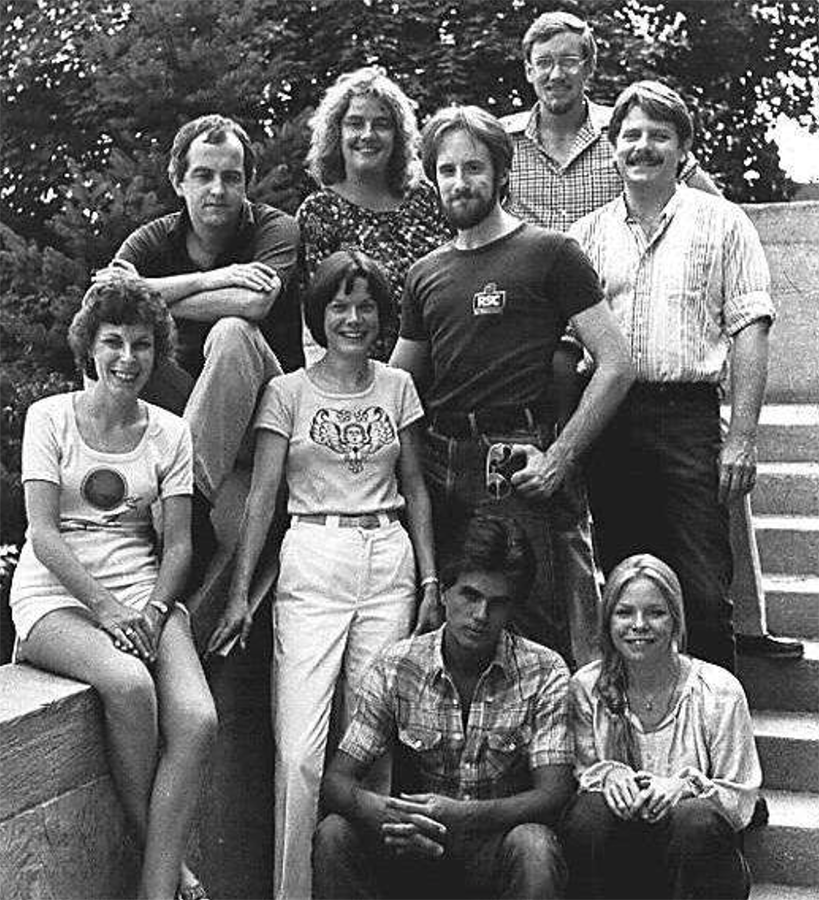

Source: Julia Royall

Royall with The Iron Clad Agreement

Alumna Julia Royall’s (DC ’73) varied interests, background, and connections have taken her to careers and continents far beyond her initial pursuits in the world of theatre. Her path from theatre to global health has a clear common thread—her passion for bringing together everything necessary to tell a compelling story. She is a producer at heart.

During her time at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, Royall pursued a master’s in English literature through the Dietrich College of Humanities and Social Sciences and doctoral coursework in theatre aesthetics/dramatic literature through the College of Fine Arts. In 1976, she took a step back from the doctoral program to cofound The Iron Clad Agreement, an experimental theatre company of actors, playwrights, directors, and songwriters who brought stories from the Gilded Age to the people of Pittsburgh.

As producer for the group, Royall pulled together the ideas, people, and funds needed to bring these shows to life. For many of these components, she surveyed the expertise of her alma mater. She looked to CMU’s School of Drama for playwrights and directors, to the College of Engineering for an understanding of how inventions of the Gilded Age worked, and to Department of English for novels to adapt for the stage. It was through these interdisciplinary collaborations that Royall was able to create productions with unique style.

Using factory loading docks, river barges, boardrooms, and classrooms as performance spaces, the group went about building a minimalist theatre without the benefit of sets, props, or costumes. Instead of expecting people to go to a traditional theatre to experience stories, The Iron Clad Agreement brought stories directly to audiences in spaces that they were familiar with. These sites could tell the stories of Pittsburgh better than any stage ever could—and people loved it.

Source: Julia Royall

Librarian Sara Mbaga carrying out a training session in information retrieval with medical students and researchers at Makerere University in Kampala, Uganda.

Recalling the group’s stage adaption of the novel, Out of This Furnace, Royall recounts how the sidewalk outside the union hall in Braddock, PA—the mill town where the story takes place—was lined with people eagerly waiting to see the show. “It was incredible. It wasn’t to see us. It was to see their story.”

From theatre, Royall began exploring other areas where she could apply her passion for telling “their story.” It was at this point that she discovered how well she fit into the field of global health and the positive difference that she could make. She began at SatelLife, a small nonprofit using low-Earth orbit satellites to improve communications for public health. The organization specifically focused on areas of the world, like Africa, where access was limited by poor communications or economic conditions.

Through this work, Royall recognized the challenges and limitations of the established paradigms in the field. Many groups seemed to either embrace a top-down approach (viewed as a colonial approach) or implement solutions that were well-meaning, but lacked local context. Royall knew that she instead needed to adopt a collegial approach to her work—one where African scientists identified their health priorities and were provided with information and communication technology (ICT) tools to address them. It was clear to Royall that better connections needed to be made between physicians across the continent.

“Research that had been carried out and published in Africa in the 90s had never been seen by people in Africa who could actually take that research and implement it,” Royall explains. “A paradigm shift had to happen.”

Royall was later recruited to the big stage of the U.S. government at the National Library of Medicine (NLM) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Her task was to create a malaria research communications network to support the efforts of researchers and scientists in Africa with critical tools. In many ways, Royall was back to being a producer, coordinating many actors, networking 24/7, and ensuring the audience was at the center of the story.

In a way, I feel I never stopped being a producer.

Julia Royall

Her passions collided once more when she saw the collegial approach she had adopted in her own work also being modeled at Carnegie Mellon University Africa, the College of Engineering’s Kigali, Rwanda location.

“I think the heart of Carnegie Mellon Africa is a collegial collaboration between a university in Pittsburgh and a young country in Africa to create something that wasn’t there before,” Royall explains. “And that something is to produce young African engineers and IT professionals and entrepreneurs who can lead the continent forward. That was pretty exciting to me, and that’s what I believe in.”

To continue to model the approach of sustainability, ownership, and autonomy, Royall created the Student Innovation Fund for CMU-Africa. The fund seeks to promote creative interdisciplinary efforts for health that bring together entrepreneurship, innovation, and information technology for students enrolled at CMU-Africa.

“It’s really important that the collegial approach gets modeled, that process of having an idea and questioning, ‘who needs to be at the table to make this idea work?’” Royall explains. “My hope for the fund is that it can model this approach. It’s really a different way of looking at development.”

Royall hopes to spread the same lessons, spirit, and mentorship she received during her time on the Pittsburgh campus to the next generation of changemakers in Africa. “It’s all about making your ideas come alive somehow and be available to other people,” Royall explains. “Also having a strong base for whatever direction you decide to go in, whether it’s theatre or global health—that’s what I feel Carnegie Mellon gave to me.”

Pictured, top: Royall as a guest lecturer at CMU-Africa. (Source: Julia Royall)