As advertised? Exposing lies about VPN locations

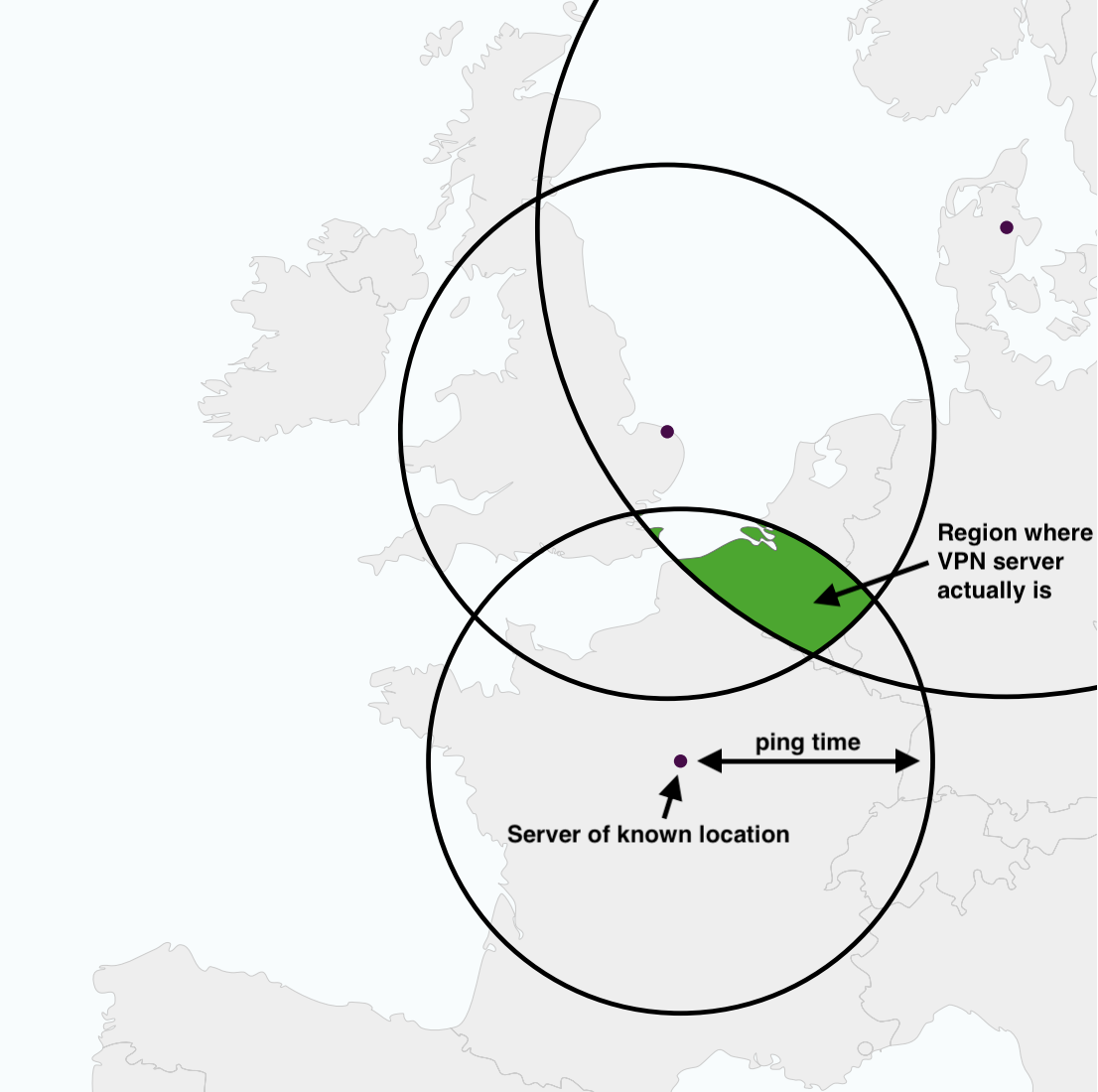

CyLab researchers figured out a way to approximate actual locations of VPN servers based on the amount of time it took for a server in the unknown location to send a packet of data to a server in a known location—generally referred to as “ping time.”

One afternoon, roughly two years ago, CyLab graduate researcher Zack Weinberg noticed something a little odd.

Weinberg was conducting a study about web censorship, using Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) to route web requests from his computer in Pittsburgh through servers located in various countries of interest in order to see what internet users in those countries were able to see online.

“If you’re in Saudi Arabia and you try to visit a gambling website, you’re supposed to get a screen that says gambling is prohibited in Saudi Arabia,” Weinberg says. “But that didn’t happen for me, even though the VPN I was using claimed to be in Saudi Arabia.”

It turns out the VPN was lying; its servers were actually located in a datacenter in Germany.

This led Weinberg to pursue a whole new study, “How to Catch when Proxies Lie: Verifying the Physical Locations of Network Proxies with Active Geolocation.” Weinberg, who is a Ph.D. student in Electrical and Computer Engineering, presented his findings at last month’s ACM Internet Measurement Conference in Boston.

Source: Zach Weinberg

Based on ping times, Weinberg and his co-authors were able to triangulate where a VPN’s server may actually be located.

Beyond research purposes, many people use VPNs to circumvent eavesdropping on their internet activity that may occur in their country or to bypass restrictions on content in their country, such as a sporting event that may be “blacked out” in their location. If VPNs lie about their location, users may not get what they want.

Weinberg and his co-authors figured out a way to approximate actual locations of VPNs based on the amount of time it took for a server in the unknown location to send a packet of data to a server in a known location—generally referred to as “ping time.”

“It’s a similar principle to GPS,” Weinberg says. “You ping a server from Pittsburgh, and you learn that it took 20 milliseconds. You do this from a whole bunch of servers with known locations all over the world, draw some circles on a map, and you can see where they all intersect.”

Weinberg and his co-authors estimated the location of 2,269 proxy servers and found that one-third of the servers were “definitely not located in the advertised countries, and another third might not be.”

One VPN service in particular claimed to have servers in almost every country in the entire world, including North Korea, and “a bunch of Pacific islands that probably don’t even have cables,” Weinberg says.

But, why would a VPN service lie about where its servers are? Weinberg says it probably has to do with costs.

“It’s definitely cheaper to have many servers in one location than one server in many locations,” Weinberg says. “A secondary benefit may be that these VPN providers don’t have to do business with a country that is difficult to do business with.”

Weinberg says that people using VPNs should be wary about the countries they claim to have servers in.

It’s definitely cheaper to have many servers in one location than one server in many locations.

Zach Weinberg, Ph.D. student, Electrical and Computer Engineering

“If people expect their data is actually going to go through this country and it’s not going to go through this other country—if they’re genuinely trying to control which jurisdictions their traffic is subject to, which is something that comes up a lot in surveillance—then this is a big concern,” he says.

Other authors on the study included Ph.D. student Shinyoung Cho from Stony Brook University, Associate Professor Phillipa Gill from the University of Massachusetts, and CyLab faculty Nicolas Christin and Vyas Sekar.