One-of-a-kind team breaks new ground

A unique collaboration within the Department of Chemical Engineering is laying the foundation for a whole new discipline of fluids engineering.

“I first met Aditya when he came to Pittsburgh for a year as an undergraduate exchange student from the UK,” says Lynn Walker, professor of chemical engineering at Carnegie Mellon University. “He was in the first class I taught.”

“The second class,” counters Aditya Khair, a fellow chemical engineering professor. “It was way too polished to be the first time.”

“Well, I’ve known Aditya for a while,” concludes Walker.

“And I still have all the notes from that class, and all the homework she graded. I’ve kept the ammunition for roasts when Lynn eventually wins all the big awards,” jokes Khair.

Today, as colleagues rather than professor and student, it’s an award they’re sharing that’s brought them together. The two have received a grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF) to explore a little-understood area of chemistry: the manipulation of surfactants in liquid-liquid interfaces using electric fields.

Source: Raj Sengupta

A drop of squalene oil containing carbon black particles and a surfactant, suspended in silicone oil. The drop deforms and breaks up as an electric field is applied.

This may sound complicated, but at its core it’s quite a simple concept. Imagine mixing olive oil with water and then shaking it, until you’re left with numerous small droplets of oil suspended in the water. This is called an emulsion, one liquid suspended in another, and at the surface of each droplet is a liquid-liquid interface—where the two liquids touch.

By adding surface-active species known as surfactants, which facilitate the manipulation of this interface, an electric charge can be applied to force the droplets to recoalesce, separating the two liquids.

The problem is that the science necessary for controlling this process has yet to be well-defined. Walker and Khair hope to provide engineers with the fundamental research, models, and tools necessary to be able to utilize these techniques on an industrial scale. Electric fields could provide much lower energy consumption and better control than current techniques that utilize mechanical mixing.

“The issue up to this point is that there hasn’t been a team with the right expertise,” says Walker. “This is one of those classic examples of Carnegie Mellon’s interdisciplinary strength, because this only works if you have a couple people working in different directions, coming from different places.”

While the two have known each other since Khair’s days as a student, their working relationship began several years ago when they worked together on another NSF-funded project. Both projects represent a perfect example of how Carnegie Mellon brings together expert faculty—with Khair specializing in computation and theory, and Walker in experimentation—along with the right resources and collaborative environment to tackle problems inscrutable almost anywhere else.

This is one of those classic examples of Carnegie Mellon’s interdisciplinary strength, because this only works if you have a couple people working in different directions, coming from different places.

Lynn Walker, Chemical Engineering Professor, Carnegie Mellon University

“It’s actually a new area for both of us,” says Khair. “I’d never really worked on drops or interfaces. Lynn had, but she hadn’t worked so much with electric fields.”

“And I’d certainly never done the theory side of it,” continues Walker, “so it’s been a very nice collaboration, bringing together two very different skill sets.”

“And,” adds Khair, “we’ve been blessed with really good students to work on this, and that’s what makes it happen.”

The student at the forefront of this most recent project is Raj Sengupta, a fourth-year Ph.D. student co-advised by Walker and Khair. It was actually Sengupta’s Ph.D. proposal that provided the catalyst for the project itself. Together, the three combined Sengupta’s proposal with the professors’ prior collaborative experience to tackle the groundbreaking work in a way no other group could.

Sengupta has already begun early experimental work for the project. While the phenomenon may seem unextraordinary when related in terms of olive oil in water, the ability to more effectively control the separation of emulsions has huge implications for industries from petroleum processing to printing.

Sengupta will spend the rest of his Ph.D. laying the groundwork for the first comprehensive foundational work on interactions between electric fields and surfactants within liquid-liquid interfaces—and ideally, creating the first surfactant designed specifically for use with electric fields.

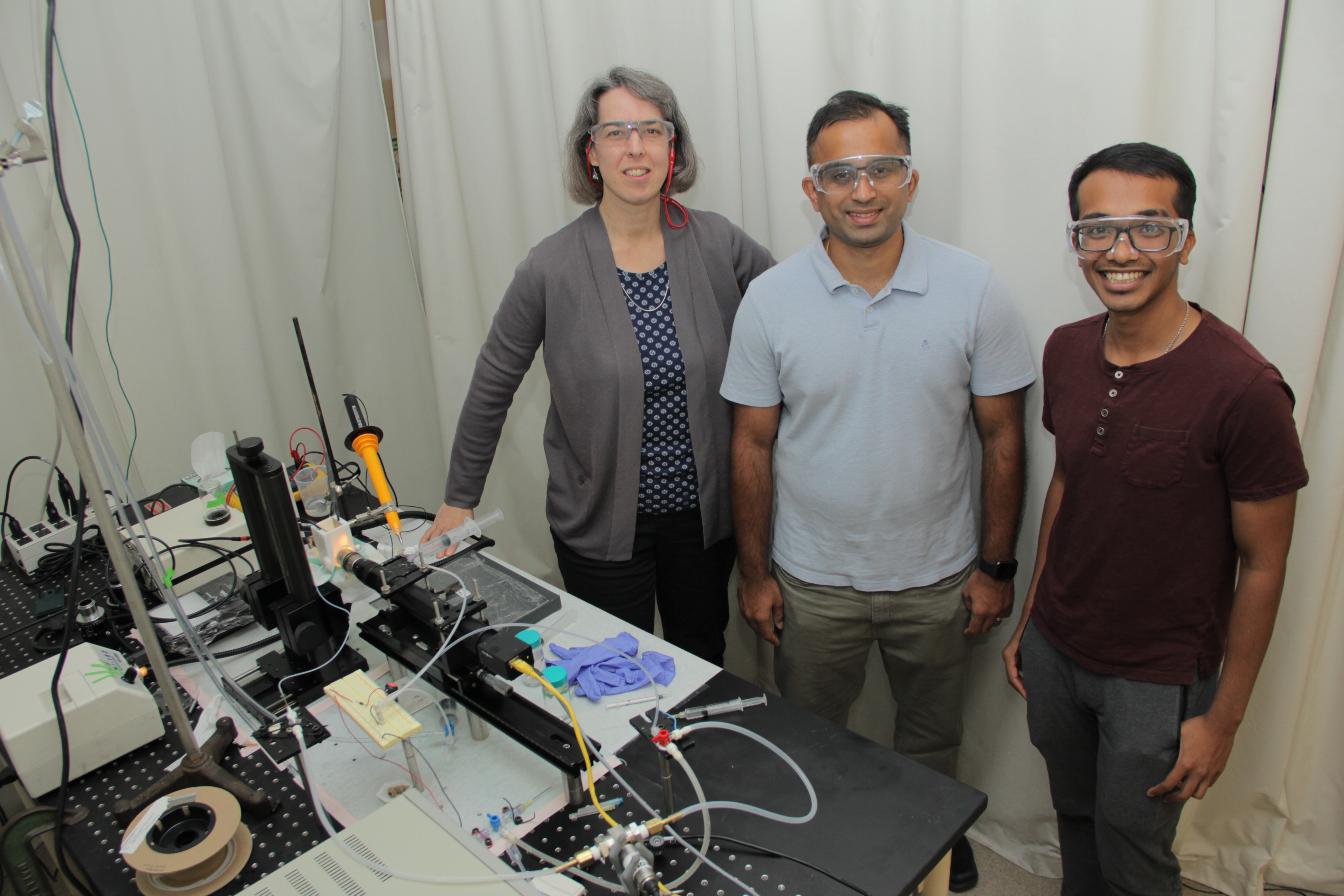

Source: College of Engineering, Carnegie Mellon University

The team with their experimental setup, from left to right: Lynn Walker, Aditya Khair, Raj Sengupta.

The work is part of a three-year grant from the NSF, an organization committed to promoting work both fundamental and applied. It represents the fourth and final corner of what makes this pioneering research possible: driven and dedicated students, experts from diverse scientific backgrounds, an institution to give them the space and resources to come together, and an organization with the vision to enable their goals to come to fruition.

“We’ve been working up to this project for a few years now,” says Khair. “We’ve worked together since I got here seven or eight years ago.”

“Right,” continues Walker. “It took one or two years to put a proposal together, and after the first project got funded, it took a couple years to figure out how to work together. Now, with this new project, we’re at the point where it’s become a really powerful collaboration.”

All work discussed was performed at Carnegie Mellon’s Center for Complex Fluids Engineering, and contributions were made by Walker and Khair’s former Ph.D. student, Javier Lanauze, now a postdoctoral researcher at the Eindhoven University of Technology.

Learn more about Aditya Khair’s other research.