Life after tailpipe

Researchers uncover the dynamic behavior of vehicle exhaust in the air.

If you see black smoke coming out of your tailpipe, you should probably see a mechanic. But researchers from Carnegie Mellon’s Center for Atmospheric Particle (CAPS) took a closer look at the stuff coming out of your tailpipe.

Cars and trucks are a huge emission source of particulate matter, a dangerous type of air pollution that can have serious health effects on humans. CAPS researchers, in collaboration with researchers from Aerodyne Research, Inc., set out to study the behavior of tailpipe emissions at the heavily traveled Fort Pitt Tunnel in Pittsburgh.

The study found that particulate matter emitted from vehicles could partially or fully evaporate in the air. The knowledge of this dynamic behavior could help inform air quality policies and regulations.

The research team first ran cars on a dynamometer. Assistant Research Professor Albert Presto, the study’s principal investigator, described the dynamometer as kind of like a “car treadmill” that helped the team measure how much particulate matter was emitted and how much would evaporate.

Source: Carnegie Mellon University College of Engineering

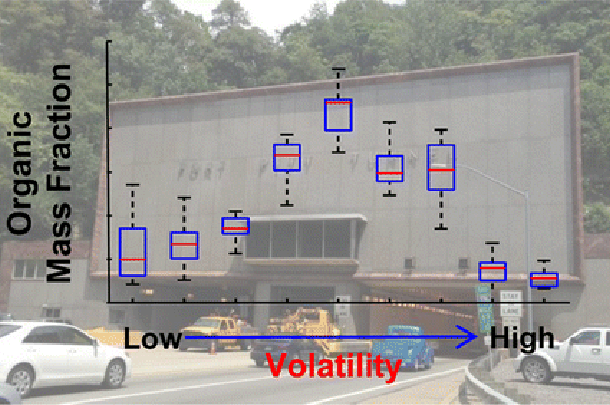

Presto's team measured the gas-particle partitioning of vehicle emitted primary organic aerosol (POA) in Pittsburgh's Fort Pitt Tunnel.

“Previous work had been done to characterize how much of these particles evaporate based on lab tests. For this study, we went into the Fort Pitt Tunnel to see if what had been observed under lab conditions also described what we found in the tunnel. We found that yes, the dynamometer tests describe what is happening when you actually drive your car,” said Presto.

The study confirmed that their lab measurements held up under real-world conditions, but the researchers also found two other interesting outcomes. First, how much of the particulate matter evaporated didn’t change with the seasons. Two, they found that most of what was evaporating was motor oil, or something very similar to motor oil.

The results of the study will help researchers more accurately represent the evaporation of particulate matter from cars and trucks in computer models. Presto says that better models can help the EPA and local agencies as they work to reduce harmful emissions and improve air quality.

“If you can improve how different sources are represented in the computational models, you will get a more accurate answer. The traditional model from 15 year ago didn’t take into account evaporation. But now, presumably, if you have a model with this evaporation built into it, the model will do a better job of telling you whether or not, going forward, emissions will go down,” he said.

Xiang Li, a Ph.D. candidate in mechanical engineering, was the lead author on the study, titled “Gas-Particle Partitioning of Vehicle Emitted Primary Organic Aerosol Measured in a Traffic Tunnel.” The results were published in Environmental Science & Technology.